Doug McGuff: Strength Training for Health and Longevity

Doug McGuff’s “Body by Science” is one of the most eye-opening books that I have read during the last few years. It made me re-evaluate my approach to training, and the results of such a shift of perspective were quite significant to me. Here I post a transcript of Dr. McGuff’s lecture on the benefits of strength training for health and longevity that he presented in the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Although this lecture does not relate to yoga per se, I know that many yoga practitioners are exploring interdisciplinary approaches to practice, so many people may find this information useful. At the end of the post, I present some ideas on how you can apply the principles of high-intensity strength training in your yoga practice.

Doug McGuff is an Emergency Physician for the Greenville Health System and an Assistant Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville. In 1997 he opened Ultimate Exercise gym where he and his instructors continue to explore the limits of exercise through their personal training of clients.

is an Emergency Physician for the Greenville Health System and an Assistant Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville. In 1997 he opened Ultimate Exercise gym where he and his instructors continue to explore the limits of exercise through their personal training of clients.

So here’s Dr. McGuff:

What I want to talk about is why, wherever you are in your life, you should take up strength training and perform it over the course of your lifetime. It’s never too late to start. And that’s the one thing I want to drive home, it’s that the physiological mechanisms that allow adaptation to strength training stimulus are preserved throughout the lifespan.

I work in emergency medicine. Emergency medicine has significantly changed over the last decades. It’s very difficult for me to articulate to you how sick the populace is. Emergency medicine used to be about crisis intervention during acute illness or injury. Now the bulk of emergency medicine became a matter of dealing with exacerbation of chronic illnesses and pulling people from the brink over and over again. And this brinksmanship got me to realize that I went to emergency medicine thinking I will be this life-saver guy, but where I’m really saving lives is in my gym.

Where you really make a difference is by keeping people from entering into that cascade of events that invoke this medical brinksmanship at the end of the road. And that is probably my more valuable activity in terms of service to humanity of the two things that I do.

There are two sides to my professional life:

- saving people from themselves late in the game

- making the above never happen.

It’s hard to articulate how sick people are. My emergency department has 20 beds. Around the clock now all 20 beds are full, we’ll generally have 6-8 people in the hallway, 20-25 in the waiting room - at 3 pm and 3 am. We used to see a lot of low acuity stuff - people were using us as a clinic because we’re required by law to do that, but now everyone is very sick. I have seen children as young as 18 months old with type 2 diabetes. You see 2 and 3-year-olds that weight 50 pounds. More than half of people in their 20 need physical assistance to sit up from being examined in lying position. So I’ve come to embrace the idea that I want to make my life’s focus more on making sure that (these illnesses) do not happen.

In my thinking, I am guided by the concept of physiologic headroom - the difference between the most you can do and the least you can do. So you start with a high physiologic headroom - and the way things go in Western society now is that you start high and that trims downward. Eventually, there comes the day where there is no difference between the most you can do and the least you can do - and when that happens, that’s called death.

So what we want is not just high physiologic headroom but a large area under the curve. So if we take the average state of affairs, people start pretty high and by adolescence, they start to decline. And it speeds up so that by the end of life you become walker-bound, cane-bound, then you are institutionalized, transitioning from living in a retirement community to assisted care to a nursing home to memory care to a pine box.

And that’s kind of become our understanding of the natural progression of aging, that’s the way it should be, that over time we should have some sort of decline. But that’s not biologically normal. What’s happening in our society is that we’re conflating common with normal. And what’s common in our society is certainly not normal.

When we think about these things, we need to ask ourselves: how old would you be if you did not know how old you was?

This is the picture of Satchel Paige, he was a black elite player in about 1926 to 1950, and he was the oldest major league rookie in the history of major league baseball entering at age 42 at 1948. He was considered the greatest pitcher of all time. This guy knows a thing or two about physiologic headroom and area under the curve. He highlights for us that there is something going on in human biology: hard demanding physical activity is a stimulus that acts upon the body which will make an adaptive mechanism regardless of your age. With that, we come to realize: this is normal. We view this as an outstanding and freakish accomplishment, this is what’s normal.

What is common is not normal. This gentleman is 75 years old in this picture. He has been weight training since 13. We look and say: he is a statistical freak, an outlier, and he must exercise from dusk till dawn. The truth is he does one high-intensity session per week lasting about 30-40 minutes, he does another high-intensity interval training (aerobic type protocol) per week and follows a very natural whole foods diet. And that’s it!

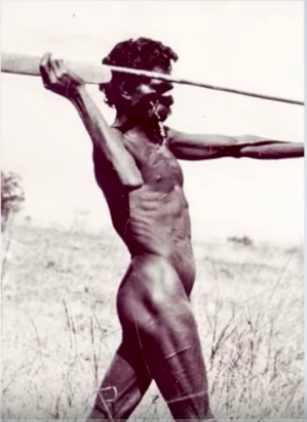

When we look at modern hunter-gatherers, if you look cross-board, they lived till about an age 72. But that average age includes in the average infant mortality and death from disease and injury. If you take those two things out of the equation, it’s not abnormal to live near 80s and 90s. And they have high physiologic headroom into extreme old age and they have a large area under the curve and this, if you know what to do, is your birthright.

This does seem extreme and unusual, but here is the modern aboriginal hunter-gatherer of the same age. So absent the dietary distortions and out of this our modern western lifestyle, this is how our physiology naturally and normally tracks as we age (what aging looks like normally). And that’s the way it should be and could be. And I wanna talk about how maybe we can make that happen.

But before we do that’ let’s revisit what is common, but not normal. It’s this.

And this is what I’m talking about when I say this is what I see every day in the ER. I have become very much expert in manipulating and tweaking very disrupted and disturbed physiologies. The disturbing thing about this is when you look, there’s not a lot of distance between the care receiver and the care provider in this picture. The woman that’s providing the care is probably 5-10 years away from switching seats.

So when we look at aging and diseases of modern civilization, as we explore them, we find that all of them seem to be related to muscle loss that occurs with improper aging. And that’s been coined sarcopenia. What we find is that all of the diseases that we don’t desire seem to track along with muscle loss. And reversal or improvement in these disease states is preceded by restoration of muscle mass and strength. So for some reasons, muscles seem to be one of the important keys (of health). And it goes beyond simply the fact that muscle produces movement and can become stronger.

When we look at the American Council of Aging, they identified 10 biomarkers of health:

- Muscle mass

- Strength

- Bone density

- Body composition - % body fat vs lean mass

- Blood lipids

- Hemodynamics - blood pressure and cardiac function

- Glucose control

- Aerobic capacity - your ability to do a low level of exercise intensity.

- Gene expression - how your genes express themselves can change based on environmental triggers

- Brain factors

We’ll hit each one of these factors individually as we go through the talk here.

1 & 2. Muscle mass and strength

I group muscle mass and strength together. Strength is independently associated with functional ability and balance. It’s in itself important. With age people become fall-prone. Just this year falls have become #1 cause of traumatic death for people of age over 65. The #1 condition that is occupying the trauma services at level 1 trauma centers is now elderly falls. Elderly falls exceed motor vehicle trauma, knife and gun trauma, and other traumatic causes. All those others COMBINED are exceeded by elderly falls now. Most people think that elderly fall because they are getting arthritic and stiff, but the real truth of the matter is that your most powerful muscle fibers (type 2 fibers) are the ones that produce a lot of force suddenly when necessary. And those are the fibers that are most prone to atrophy and go away with disuse. So what happens when I’m standing in perfectly straight lined up with gravity posture, I’m good. But you lean forward a bit - it’s completely unconscious to anyone functioning well, but those type 2 fibers kick in, contract hard, and right you. It’s not joint stiffness or loss of reflexes that make the elderly fall, it’s the loss of those higher order type 2 fibers. So when you lose your centering of gravity and take the long lever of your body, you don’t have the power to bring it back to upright. So strength is important in and of itself.

But more importantly, what we’re finding out, and this has just been in the past few years largely by the research of Bente Kharlund Pedersen in Europe, that skeletal muscle turns out to be our largest endocrine and immunologic organ in our body. In the same way that your pancreas sends out insulin and control glucose balance, your muscle is sending chemical signals out to all the different tissues of your body, saying that “I’m still here and we need you”. Those signals are very important and that’s why strength training seems to produce benefits that are so much greater than just the sum of its parts.

30% loss of strength over 12 years in the elderly was restored in 1 year of strength training. And that was a 30-50% increase in strength from when they started. And I can tell you from my shop - we train lots of elderly folks - that is very modest. So this is strength training that is poorly done, producing dramatic results. Really well-done strength training makes a really massive difference.

Bending the aging curve

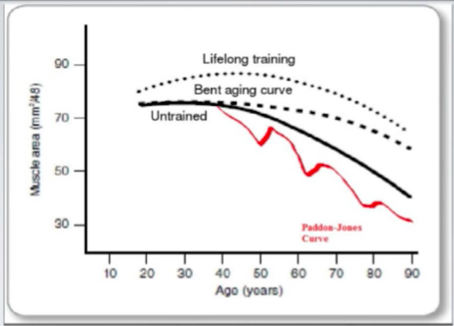

So let’s look what it looks like. This is the aging curve that was first put forward by Joseph Signorile, he’s in the University of Miami. And what he’s showing here is the difference between the dark black line which is just your untrained curve in western society, this is how your area under the curve looks like in normal circumstances. Someone who starts training early in life is going to have this training curve that goes upward, to around age mid-50s, and then starts a gradual trend downward. And then there’s a bent aging curve of someone who takes up training in their 50s and how that is deflected upwards. I can say from my experience of training older clients that that bent aging curve with optimal strength training protocols hugs up more against lifelong training curve. You can make up that gap if you’re vigilant about bringing a powerful stimulus to the body. Now that red line is actually a colleague of his, Paddos-Jones came to him and said: look, that untrained curve is actually much worse. You’ll have these little periods when there are sharp declines in functional ability, some recovery, then again and again, and I’m living in an emergency room at those sharp little deflection peaks. That’s what those represent. And that’s what I’d like to see never to be necessary.

To put it more visually, this is a "use it or lose it" visual representation. The top picture is of a 40-year-old triathlete - not the optimum physical activity for maintaining muscle mass necessarily. The middle picture is of 74-year-old sedentary man, the bottom is a 70-year-old triathlete. What I want you to pay particular attention to is the ratio of muscle, which is a grey tissue - to fat which is the white tissue on the outside, and how similar the top and bottom look to each other despite the age difference. If anything, the 70-year-old triathlete is actually carrying less body fat. But when you look at the bone mineral density, the 70-year-old triathlete is as good or better than our 40-year-old triathlete. As compared to the sedentary person, you can see the incredible loss of bone mineral density, the atrophy and how much body fat is there.

That ratio of body fat to skeletal muscle becomes important because each of the body tissues to some extent exists in competition with each other for resources. And once one of those tissues gains a competitive advantage, so to speak, energy utilization gets channeled towards the preferred tissue. So when you become body-fat-dominant, you start to accelerate the diseases of aging, because body fat generates lots of inflammatory cytokines, lots of chemical messengers that produce inflammation in the body that accelerates aging, accelerate tumorigenesis. It’s just not good stuff. So you want to create a situation where you’re giving skeletal muscle the competitive advantage.

And when I saw this, it triggered the memory that I had working as an emergency physician looking at lots of CT scans. And when I was a younger person, I always had a notion that if someone was obese, that was kind of like chronic weight lifting. So I expected the musculature underneath to be bigger as a result of carrying that load over time. But the amazing thing, what a CT scan is, you put the person on the table, it’s sort of an X-ray representation looking at you at cross-section as if you were a ham. And I was picking up one slide at a time and looking at it. What I’ve noticed is that in the morbidly obese, skeletal musculature is incredibly atrophied. Particularly the external oblique muscles here on the side, you see people come in with this phantom thing - pain that nobody can figure out, so you look the CT scan, and external oblique muscle is paper-thin. And because of the inter-abdominal fat, it’s stretched to the point of bursting where it attached to the hip bone at the point on iliac crest. It’s very counter-intuitive until I understood the relationship between myokines and inflammatory cytokines that we’re going to discuss here.

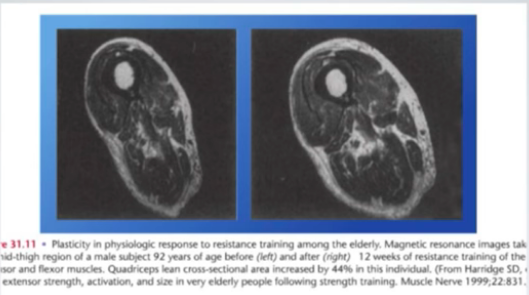

So we showed triathletes, but the response to strength exercise is even more dramatic. This is a representation of a 92-year-old male subject after 12 weeks of resistance training confined only to his leg musculature - leg extension and leg curls, with what I perceive as an expert in delivering a stimulus, is a fairly poorly delivered stimulus. But what you see is a dramatic increase in muscle mass, and improvement in bone mineral density, just in 12 weeks, that’s 3 months and that’s a big reversal of skeletal muscle mass loss.

Summary of how strength training impacts muscle mass and strength:

- Strength is independently associated with functional ability and balance.

- Skeletal muscle is our largest endocrine and immunogenic organ

- 30% loss of strength over 12 years in the elderly was restored in 1 year of strength training.

3. Bone density

If we move on to bone density, the exercise protocol that I use in my facility had its birth right in this region. In early 1980s Arthus Jones and Nautilus wanted to do research on strength training and how it would benefit women with osteoporosis. They partnered with the University of Florida, set up a strength training research project. They sough to deliver high-intensity strength training to women with advanced osteoporosis, but they had to come up with a protocol to protect them against force because they were frail and fragile, they did not want to injure them. So they had this idea of lifting the weight really slow to control acceleration (remember that force is mass times acceleration). So that’s how we keep the force low enough to be safe. And what they saw was a rate of strength improvement that was greater than they expected. They thought, well, maybe they are just making up for the lost ground. So they tested in younger populations and found that the rate of improvement was also better there. It turns out that because slow movement protocol kept them under continuous load all the way, it invoked a rapid and deep level of fatigue very quickly, and that seemed to be the stimulus.

So Arthur Jones knew intuitively that something about strength training went beyond the mechanical stress on the bone that was producing these results. Now we know that these adaptations are largely due to myokine signaling, especially the one called Interleukin-15 (IL-15). So hard-working skeletal muscles send out this hormonal signaling to the bone saying “Hey we’re strong and we’re attached to you so you need to be strong too”. And that seems to be the signal. The cool thing is that this is completely separate from the loading aspect of the equation. You can take IL-15 in vitro and bone density will increase irrespective of any loading. So chemical signal in and of itself seems to be important.

Summary of how strength training impacts bone density:

- Strength reductions precede osteoporosis

- Strength increases predict improvement in bone mineral density

- Used to be thought to be due to mechanical load/stress

- Now we know it to be largely to myokine sygnaling (IL-15)

- You don’t have to risk a fracture to increase bone density.

4. Body composition

So now we’ll talk about body composition. It’s become quite common to say lately it’s not just calories in/calories out, but that is very true, because like we discussed before, your body tissues are in competition to each other for nutrients, and myokines released from skeletal muscle while doing hard intense work offer advantage towards lean muscle.

When you load muscle aggressively, when it's rapidly fatigued, and you produce a momentary weakening of that muscle, that biological signal says:’ We are the priority. Nutrients need to flow towards us, not towards body fat”. And again, it seems that IL-15 seems to be leveraging this battle, but there are other things going on there. The earliest myokine ever discovered was called IL-6 (interleukin-6). It was a big player in inflammation and cancer. It was thought to be a bad boy. And during intense exercise, it would go up in a spike to almost a 100-fold. And everyone who looked at it was like, “Oh, this can't be good. Better back off and take it easy.” But as more research was done, what we found out is that a big spike was actually a good thing, because the receptors of IL-6 down-regulated as the result of the spike. So over time, your circulating level of that hormone went down. So the net benefit of that time was a decreased level of inflammation. But that myokine also increased fatty acid uptake from your fat cells and metabolism, it increased glucose uptake (glut4 receptor) and utilization within the cell. And that therefore modified insulin signaling similar to what the hormone leptin does and by that virtue also decreased inflammation.

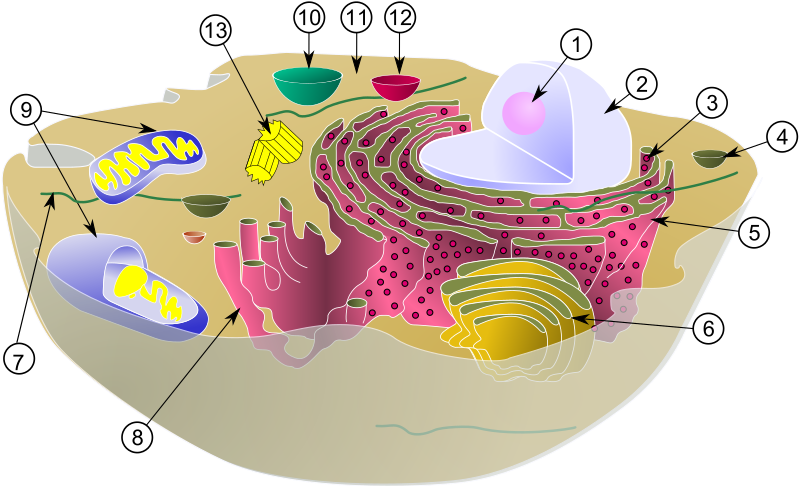

IL-15 is involved in signaling your existing fat cells, it triggers a chemical called Uncoupling protein to convert your white fat which is purely an energy storing depot and generator of inflammatory cytokines into brown fat, which basically takes the mitochondria, the little powerhouses of your cell, and pulls the generator plug on, so that the energy that’s produced through mitochondria is now thrown off as heat. And that is permissive towards burning off more of your body fat for a more ideal body composition. So, the contribution of these hormones released by muscular activity enhances your body composition.

Summary of how strength training impacts body composition:

- It isn’t just calories in/calories out

- You body tissues are in competition with each other

- Myokines shift the home field advantage toward lean muscle

- IL-15 leverages the battle

5. Blood lipids

So next is your blood lipids. THis is huge in medicine, but really the numbers that they talk about, the ones that you normally get at your doctor’s office are very loosely associated with the cardiac disease as they kind of just measure total cholesterol, they measure your HDL cholesterol, they subtract your HDL from your LDL and then infer things about it. And it may be relatively meaningless. What’s more meaningful is the particular particle type of LDL you have, certain genetic factors like your APOE type, but strength training is known to raise HDL and lower LDL. But that’s not the real issue when it comes to cardiovascular disease. The more important is the way in which it opposes the inflammatory myokines (cytokines) and controls insulin sensitivity and serum insulin levels. And that’s very protective against cardiovascular disease.

Summary of how strength training affects blood lipids:

- Know that your numbers VERY loosely associated with heart disease

- Strength training raises HDL/lowers LDL

- More important: controls insulin and opposes inflammatory cytokines.

6. Hemodynamics

Next up is hemodynamics. This is where strength training really shines over aerobic or steady state activity even though the latter has kind of really become the darling of cardio-vascular improvement to the extent that we don't even say “aerobic”, we say “cardio”. But that’s not even true.

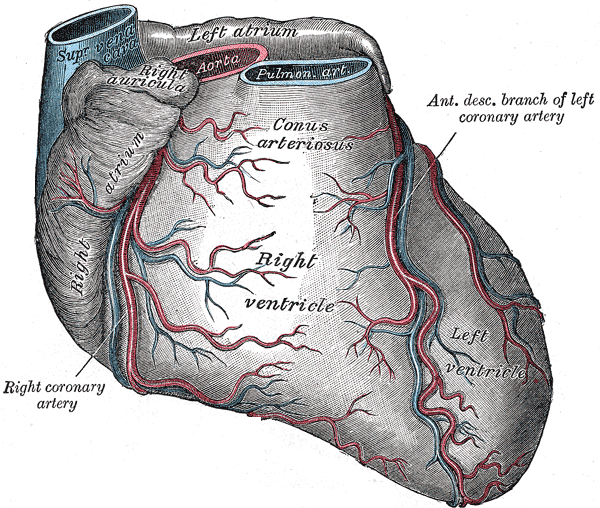

Starling’s Law of the Heart is a physiologic law that basically describes how the heart functions. Probably the simplest way that I can put the point across is that your heart is like your septic system. It’s like a sub-pump. It works if the volume dumped on the input side equals the volume on the output side. So your cardiac output out of the left side of your heart - how much blood gets pumped out with each heartbeat - is directly proportionate to the amount of blood delivered on to the right side of your heart. So 500 ml goes in this side, 500 ml gets pumped out on the other side. Now, we all know our coronary arteries are important. They come off the base of your aorta they go out to your heart muscle, and they supply the blood flow to your working heart muscle. So what happens it, the volume of blood that goes to the right side of your heart equals the volume of blood that’s pumped out the left side of your heart, that pumps forward during systole. During the relaxation phase of your heart, a portion of that blood volume washes back to the base of the aorta floods the coronary arteries and determines your coronary artery blood flow.

What a proper strength training does is this. Blood return to your heart is very passive. Below the level of your heart, how venus blood gets there, is through a muscular contraction, in a one-way valve network that allows that blood to be pushed back towards your heart. That is very much enhanced by intense muscular contraction. Intense muscular contraction done during this type of training milks venus blood to the right side of the heart, enhancing the volume that’s pumped into the right side of the heart, which therefore enhances the volume that’s pumped out of the left side of the heart which therefore enhances the backwash that floods the coronary arteries and determines coronary artery blood flow.

I began to appreciate this because early on when I opened my gym I had several clients that known advanced coronary artery disease, who would develop anginal chest pain walking over to their appointment from one block over. But I could take them through an entire high-intensity strength training workout to complete muscular fatigue - five separate movements in fairly rapid succession - and they would not have angina. And I think that that is because this enhanced venus return enhances coronary artery blood flow. I don’t know this, I can’t prove this, but I believe this. There is a treatment modality for people whose anatomy of coronary artery blockage is not conducive to stinting or bypass. They have no hope. It’s called External Counter Pulsation Therapy. It’s basically big bladders like a blood pressure cuffs that are put on your lower extremities and they inflate and deflate in a rhythmic pattern that pump venous blood back towards the heart, and what they have found is that it’s almost like a physiologic bypass. That enhances coronary artery blood flow and causes opening of existing blockages and alternative pathways to develop around blockages, and is a treatment for inoperable coronary artery disease. I think that high-intensity strength training probably invokes that kind of mechanism, and I think it’s a fertile ground for research that I would like to see happen.

The other thing that happens over time is that we know that chronic hypertension causes cardiac and vascular damage. And IL-6 stimulates neo-vascularisation, which basically means new blood vessels to supply nourishment to the working muscles. What that does is by laying down more pipe, you increase the volume of container that blood volume is contained in. So a given volume in larger vessel results in lower pressure. It decreases your systemic vascular resistance and in turn, decreases your blood pressure. IL-6 also stimulates the release of nitric oxide which causes vasodilation and increases blood flow in the skeletal muscle that has a more long-term effect of modulating blood pressure towards more optimal levels.

Now in my shop, it’s very common that we have people starting in their mid-30s that are on lisinopril or hydrochlorothiazide or some sort of first stage anti-hypertensive drugs. And it is very common that within 12 weeks they are becoming hypotensive on that medicine, and have to go off of it. and I think this is probably a mechanism for it.

Summary of how strength training affects hemodynamics:

- Starling law of the heart

- Enhanced venous return

- Enhanced stroke volume/coronary artery perfusion

- Decreased systemic vascular resistance

7. Blood glucose control

So there’s big blood glucose control issue. Outside of the myokine aspects of things, one thing that we want to know about a skeletal muscle is that it is the biggest glucose reservoir in our body. And we tap into that glucose stored in the muscle for on-site usage during emergencies. Glucose stored in your liver is there to keep your blood sugar normalized. So when you do high-intensity strength training, you are cleaving off glycogen glucose molecules through something called an amplification cascade. That means, adrenal molecule comes in, binds into one co-factor which binds a thousand, that thousand bind a thousand, and that thousand bind a thousand, so the effect of one molecule of adrenaline amplifies the effect of cleaving off glucose molecules off glycogen exponentially. When you empty glycogen store, it has to be replaced, so it demands improved insulin sensitivity, improved glucose transport into the working muscle cell, and it invokes the antithesis of the metabolic syndrome that occurs when we eat a bad diet and become sedentary. And this is completely outside the myokine effects that we discussed previously.

Summary of how strength training affects blood glucose control:

- exploits and ancient adaptation: fight or flight

- muscle as the major glucose reservoir

- amplification cascade

- invokes the anthithesis of the metabolic syndrome.

8. Aerobic Capacity

So, aerobic capacity. This si not cardio. Cardio became a term in the early days of exercise physiology, the only measurement tools we had was VO2 Max. Which is a tight fitting mask with some hose that measures your oxygen utilization while exercising. So you were kind of forced to use a certain modality of exercise because it was the only measuring instrument you had. And it showed health benefits, and those health benefits got attached to aerobics, which thus became “cardio’. What we are finding out is that aerobic subsegment of metabolism gets its substrate from anaerobic metabolism. Anaerobic metabilism occurs in the liquid portion of the cell, cytosol. It’s very ancient. When the slime first started forming n the early days on earth, you had single cell organisms with just cytoplasm. They took glucose, they matabolized it through that primitive pathway they call glycolysis, the end product of which was a chemical called pyruvate. And that was a waste product. During evolution, little proto-bacteria came to being. And those proto-bacteria infected these cells, but conveniently these prot-bacteria consumed pyruvate as their food. They could take pyruvate and in the presence of oxygen, which was then becoming present in the earth’s environment, they could metabolize that pyruvate into energy. Well, those things over time got permamnently incorporated as organnelles within the cells that we now call mitochindria.

The thing is, this is where aerobic metabolism happens. But aerobic metabolism cannot happen without anaerobic metabolism delivering its substrate and here’s the catch: anaerobic metabolism can deliver to the mitochondria pyruvate at a rate faster than mitochondria can handle it. So really the only way by which you can maximally improve aerobic capacity is by doing hard exercise that invokes anaerobic work that delivers that substrate as fast as it can handle it. When you get to that point, pyruvate can no longer go into mitochindria, another enzyme called lactate dehydrogenase acts upon it, converts pyruvate into lactic acid. Which everyone thinks is a bad thing - you burn, you get fatigued, you wear down - but a properly conditioned individual, and especially properly conditioned individual that is on the diet that allows him to make a lot of ketones, can take what everyone else perceives as chemical that’s causing them to flame out, and use it as a rocket fuel. There is a biochemical pathway called Cori Cycle that can take that lactate, take is back to the liver, turn it into glucose that’s available on the more slow-burn-type basis, and kind of act almost like an afterburn kicking in for a properly conditioned athlete. So it this way strength training gets at aerobic capacity in what we now feel like a very non-traditional means.

Summary of how strength training affects aerobic capacity:

- not “cardio”

- aerobic subsegment of metabolism gets its substrate from anaerobic metabolism

- adaptations that seem to be central are actually peripheral.

9. Gene expression

This is a biggie for me. A few years ago, I dug through PubMed literature looking for something interesting, and I found this. In 2007, Dr. Simon Mуlov in the University of Southern California published an article with the title “Resistance exercise reverses aging at skeletal muscle tissue”. He used a technique called a false discovery rate to find genes in humans that were expressed differently in youth than they are in old age. And he found close to 500 genes that were differently expressed and then he took elderly people and put them through a strength training that resulted in a 50% strength increase. In high-intensity strength training, we are used to seeing 200%-300% strength increases. But with as modest as 50% strength increase, 179 genes reverted to aging reverted back to their youthful levels of expression.

And I thought: THIS IS IT! This is earth-reversing research. What happened next was - crickets, nothing! I could not believe it! Our oldest literature in human history is the story of Gilgamesh which is about finding the fountain of youth. 15 years ago they found that resveratrol can extend life in - earthworms! - and the stuff blew off the shelves! For the first time in human history, we said - we can reverse aging at the molecular level - and nothing happened! It was mind-blowing to me and this needs to get out. I’m not an investigator, I don't have to hold back and play conservative. I can tell you: this is a big deal! This is important, and there are bigger deals to come. There is technology going on with stem cells and other technologies that are going to be able to extend our lifespan. And it's great. But for a guy who is 54 years old, I gotta say: “Is that gonna come to fruition in my lifespan?” And you may wonder the same thing, but I gotta tell you, if anything is going to bridge the gap, this is it (the strength training), this is what buys you time until that happens.

Summary of how strength training affects gene expression:

- Dr. Simon Melov identified 179 genes related to aging that reverted back to youthful levels of expression from 26 weeks of strength training.

- First successful reversal of aging at the genetic level in humans

- This was based on a strength increase of 50%, which pales in comparison to high-intensity strength training.

10. Brain factors

Lastly, brain factors. One of the myokines is the brain-derived-neurotrophic factor (BDNF), the memory myokine. Like love, you don't really appreciate it until it’s gone. And it is low in Alzheimer’s, depression, obesity, and it’s an independent marker of predicting mortality. This stuff’s going out - you’re going to be dead soon. It’s increased in skeletal muscle with exercise. It’s good in aerobics and has an even stronger effect in strength training. There was a suspicion that BDNF produced in the muscle is only for local use and does not cross the blood-brain barrier, but my suspicion is that yes, it’s local, but it’s acting through some sort of intermediary that does cross the blood-brain barrier and thus affects BDNF levels within the brain. It certainly sounds like a good thing to me.

Summary of how strength training affects brain factors:

- BDNF: the memory myokine

- Low in Alzheimer’s, depression, obesity, an independent marker of mortality

- Increased in skeletal muscles due with exercise

- Aerobics good - strength training better.

How to do the high-intensity strength training

So we've covered all these 10 different factors that affect aging, and strength training addresses all of them. And the cool thing is, when you apply this protocol, in simplest terms, it’s lifting and lowering weight in a controlled fashion. You start the lifting with a slow gradual upload, and then you just try hard, you lift and lower and make sure that the muscles are under continuous load. What matters is that you are putting yourself under load in a challenging way, and lifting slowly and smoothly with an intent of not making something heavy go up and down as soon as possible, but with an intent of using that heavy thing to invoke a deep level of fatigue quickly. When you do that, it is an intense and unpleasant experience, but the cool thing is, by necessity, it’s time-efficient because you can’t stand more than 15 minutes of this.

The other way it’s time efficient is once you invoked a stimulus on the body, you’re asking the body to make an adaptation whereby you are synthesizing new tissue de novo, and all of the metabolic substrate and other body tissues that support it. As a consequence, that takes time. Most people have it in their head that exercise directly produces changes in their body: the ab roller will firm and tighten your abs - it’s not that way. Exercise is a stimulus perceived by your body as a negative threat of weakening your muscle from a starting state to a significant percentage weaker - 40-50% weaker than you were 90 seconds ago. To your muscle, that’s a big deal. And the adaptation is, next time I’m gonna be stronger. But the cool thing is, that adaptation takes time. And if you bring the stimulus back before that adaptation is complete, you’ll interrupt it. So 15 minutes is a necessity twice a week, once a week, depending on the person. When we go back to that 75-year-old gentleman I showed you, and you think, he is a Jack Lalane type, he exercises all day, No, that’s not even required. Actually, the opposite is required. If you do this, that’s what’s required, and done over the lifetime, that expands the area under the curve.

Summary on how strength training affects your health and longevity:

- Strength training addresses all 10 biomarkers of health and aging

- By necessity is time-efficient

- Increases physiologic headroom

- Done over time, expands the area under the curve.

(end of Dr. McGuff's lecture)

What’s the relevance to yoga?

First, if you are convinced at least partially by some arguments presented here, you might consider complementing your usual yoga routine with the strength building elements that will increase the number of advantages you can derive from physical practice in terms of health and longevity. By default, Doug McGuff presents a training protocol that involves training on the machines. But it’s not the only way to incorporate strength training into your practice. In fact, he has a video presenting alternative practice protocol for those people who have no access to a gym or no desire to train on machines. This protocol involves holding static timed contractions in an isometric fashion, contracting muscles against immovable resistance. These exercises involve using yoga belt and yoga blocks to provide that immovable resistance and in fact, they are similar to static strength exercise practiced in yoga, especially in Iyengar classes when they use these types of props. I embed the video of Doug McGuff explaining the exercises herewith, but once you get the idea of applying isometric contraction to maximally challenge your muscles, you can come up with your own yoga-based exercises that will help you simulate similar muscular and metabolic adaptation.

For example, performing very slow “yogic pushups” until the point you cannot make any more with good form, holding side planks or one-legged chair pose will help you achieve similar muscular inroad. In this way, you will be paying more attention to static strength asanas in yoga and you will have a better idea of why it’s good to hold them for at least 45 seconds. You can use yoga strap or blocks to modify usual asanas in more isometric modalities or use any other modifications of your practice based on these principles. But first, try Timed Static Contraction protocol exactly as instructed by Dr. McGuff to understand exactly what level of exertion and fatigue you are looking to achieve and observe how many days your body will take to recover from such workout.

Personally I am using Timed Static Contraction training exactly as instructed in Dr. McGuff’s video and complement it with a few exercises focused on abs (slow dynamic high-low boat or static low boat, side planks or cross - knee planks (touching your knees to opposite elbow in plank - either slow dynamic or long holds, etc.). I do this type of training once a week and it takes me about 15-20 minutes total.

In between these training sessions during the week, I do low-intensity practices that can include the following:

- myofascial work (yoga asanas, somatics, pandiculation and massage with tennis balls and basketball);

- meditation and breathing exercises;

- light plyometrics (nothing fancy or extreme, especially if the body is still sore from HIT. I see the main purpose of these exercises in training the elasticity of fascia);

- beginners' calisthenics in low-intensity mode;

- yoga balance poses for training the stabilizing muscles;

- occasionally, when I feel like - sprints and high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

The point is not to think that if you're doing high-intensity strength training once a week or so, you cannot do any other type of practice because of recovery time requirements. You can do other things, particularly because most of the activities will not match in intensity to the training presented by Dr. McGuff. However, it's important not to force yourself and not to overtrain, observe your body to understand that it is ready and wants to move. Dr. McGuff says that during the week you need to have more days above the baseline that below it. By using these principles you can create an individually meaningful training regimen that will fit your goals, capacities, and preferences.

Personal Website of Dr. Goug McGuff

blosmart

В «семью» могут входить, например, «умные» выключатели, пылесосы, замки, пожарные сигнализации, камеры, системы вентиляции . Встречайте, это блог об умных домах . По ссылке прочтите правду статьи об умных домах открытые сведения и умалчиваемые нюансы.